I’ve invited a number of people who have published in indie press to write about their experiences. Today’s post comes to us from Lee Battersby, a well-known name in the Australian speculative fiction field.

I’ve always loved short stories. My first SF book — which I still own, thirty mumble mumble years later — was a collection called SF Stories for Boys put out by Octopus Books in the 70s. I met Asimov for the first time in that book, and Harry Harrison, and began a thirty year obsession with a just-about-forgotten Australian author named Frank Roberts, whose story “It Could Be You” freaked the bejesus out of me, as well as foreseeing the logical extrapolation of reality TV forty years before the proliferation of shit-awful Mastersurvivorbrotherloser clones forced me to join Murdoch’s evil Pay TV empire.

I’ve always loved short stories. My first SF book — which I still own, thirty mumble mumble years later — was a collection called SF Stories for Boys put out by Octopus Books in the 70s. I met Asimov for the first time in that book, and Harry Harrison, and began a thirty year obsession with a just-about-forgotten Australian author named Frank Roberts, whose story “It Could Be You” freaked the bejesus out of me, as well as foreseeing the logical extrapolation of reality TV forty years before the proliferation of shit-awful Mastersurvivorbrotherloser clones forced me to join Murdoch’s evil Pay TV empire.

When I began writing, properly, because I wanted to be a writer, I wanted to write short stories above all. My first publication — a poem — was in 1989, and I’ve written just about everything in the last 20 years: poetry, stand up comedy, jokes, advertising copy, educational material, interviews, reviews, articles, theatre, film scripts, late notes, apologies, novels, death threats, legislation, instruction manuals… But I always come back to short stories. I love to read them, I love to write them. I love to edit collections of them. And when I’m gone, and nobody remembers who I was, and those who do remember are pretending not to so people won’t pity them, I want just one “It Could Be You” left behind to fuck up the mind of someone young in my name. Consider it my black-hearted little gift to the Universe.

Somewhere, whilst I was growing up in small-town Australia, the publishing world changed when I wasn’t looking. The SF magazines that had been the bastion of alternative expression during my youth — all those second hand copies of If and Galaxy and New Worlds I’d been sniffing out — went broke, and those that remained became increasingly conservative. By the time I hit Uni aged 18, every copy of Analog I read felt like every other copy of Analog, and so did Asimov’s, and F&SF, and they were the only ones I could find on a newsstand. Conservative ideas expressed with the most conservative words, in ABC plots where nothing was wild, nothing was untamed, and the ghosts of Sladek and Aldiss and Bester were long forgotten. I’d grown up with the understanding that art existed to push the envelope of what was conceivable, and even if I couldn’t yet articulate it, I could point to Gahan Wilson, to Spike Milligan, to Alice Cooper and HR Giger and David Bowie and Charles Addams and Rene Magritte and shout, “Them! It’s meant to be like them!”

Art is not comfort food. Art should never be comfort food.

But everything I read tasted like the literary equivalent of a microwave cheeseburger: glaggy, half-cooked, and deeply, deeply unsatisfying. And soon enough, you end up sitting on the couch wondering why the hell you spent money on something so awful when, if you’d expended a little bit of effort, you could have made something much more enjoyable from scratch.

In 1990 I bought the first issue of Aurealis in a little newsstand in the centre of Perth because my bus home was late and I ran out of reading material. And promptly had an “It Could Be You” moment. For the first time since I was nine years old, SF fucked me up again.

Not because the stories were at the cutting edge of brilliance (although I remember them as being, on the whole, pretty good). But because they were Australian. There was no internet in 1990, no online ordering, no e-zines, no way for me, as a poverty-stricken student (And I was poor. Bloody poor. Ask me about it sometime) to connect with an SF community: I couldn’t even afford the membership dues for my university SF club. So all I had to go on was what I read, and there was nothing, not a bloody thing, to indicate that Australians wrote SF. Like acting careers and joining the space program, it was just something other people did. In my world, in my family, you didn’t hold such hopes for yourself. My family and I, well, these days the best you can say is that we share the same basic genetic structure and we live on the same continent.

It took me eleven years of doing other things, but when I started writing SF with a sense of purpose in 2001, I aimed for Aurealis. And in doing so, I connected with an SF community that shared my passion for that mad, wild, alternative SF style that had fuelled my childhood imagination (I discovered The Goon Show the same week I was given that first SF book. And people wonder…). One of the writers from that first issue of Aurealis is now a good friend, one is a peer I look up to and whose works continue to inspire me, and one I still see at the occasional convention. But we know each other, and can sit and share a drink should we so choose. It’s hard for people within our genre, I think, to understand how special that is, to be able to form a relationship with an artist outside the scope of their work: we take it for granted because the SF genre has created a tradition of conventions and intimate contact, but there’s still something visceral for me, as an artist who still aspires in so many ways, to share space with those who serve as pathfinders for my own artistic ambitions. And those writers I first read in 1990 are all still writing short stories, and all still stretching the boundaries of what they can accomplish in the short form, in their various ways.

But why the fascination? Why do I still write and read so much in the indie press? For the same reason why my workmates have never heard of the bands I listen to, or the comics I read. Because the core of the genre has become conservative, and the government of our thoughts has become centralised, and the walls of the establishment have become higher, and thicker, and more soundproof. Outside, where the barbarians live, in the small presses, the chances of failure are greater, and the readership is smaller, and an artist can look at the world in a way that scares or damages or inspires the wild thoughts of others, and find a home for those thoughts without worrying what effect it will have on their market penetration. Because the fringe is where the fun is. Magazines live and die like mayflies. Entire careers flourish, flower, and die without a single book deal being struck. Chaos is part of the dynamic. Chaos is part of the charm.

And I love it. I love it all. I love it to the detriment of my career: my peers, those who sold their first stories at roughly the same time as me, and whose careers have similar time lines, are striking those book deals, and publishing their novels, (And good on ’em, too. Just because I love shorts, doesn’t mean I don’t want one of my own) and I have, in many ways, fallen behind them. But I keep turning on the computer to find the guidelines for an anthology of gay-werewolf-pilot stories staring me in the face, and as much as I don’t want to, as much as I know I should be adding another 10 000 words to the novel-in-progress instead, still I wake up one morning and think, “If he’s only gay when he’s in wolf form…” and off I go again.

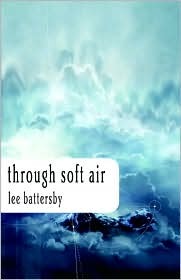

Lee Battersby is the multiple-award winning author of over 70 stories, in markets throughout the US, Europe and Australia. A collection of his work, entitled Through Soft Air, has been published by Prime Books. He currently lives in Mandurah, Western Australia, with his wife, writer Lyn Battersby, and an ever-changing roster of weird kids. He currently divides his writing time between novels and short stories, and tutors the SF Short Story course for the Australian Writers Marketplace Online. He can be found at www.leebattersby.com and is unhealthily addicted to Lego and Daleks.

Lee Battersby is the multiple-award winning author of over 70 stories, in markets throughout the US, Europe and Australia. A collection of his work, entitled Through Soft Air, has been published by Prime Books. He currently lives in Mandurah, Western Australia, with his wife, writer Lyn Battersby, and an ever-changing roster of weird kids. He currently divides his writing time between novels and short stories, and tutors the SF Short Story course for the Australian Writers Marketplace Online. He can be found at www.leebattersby.com and is unhealthily addicted to Lego and Daleks.